“Looking out my window

I see my world has changed

The sun won’t rise this mornin’

‘Cause my baby’s gone away

Yesterday I could tell myself

That she’d be back for sure

But that train don’t stop here anymore

Anymore, anymore” – Cesar Rosas / Leroy Preston © BMG Rights Management

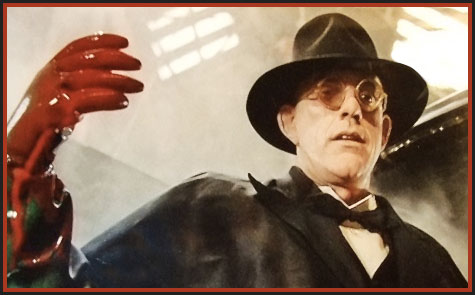

Street kid: “Hey Mister, ain’t you got a car?”

Eddie Valiant: “Who needs a car in LA? We got the best public transportation system in the world!”

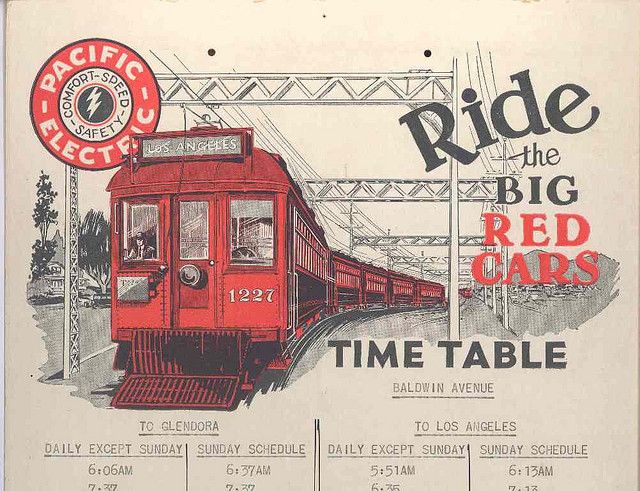

The above exchange is from a scene that takes place early on in the Touchstone Pictures film, Who Framed Roger Rabbit. In the scene, private detective Eddie Valiant – portrayed by British actor Bob Hoskins – has just hopped a ride on the rear of a passing Pacific Electric red car, where a couple of street kids have already helped themselves to a ride of their own. While Valiant’s statement foreshadowed a key plot element of the film, it was not just incidental hyperbole.

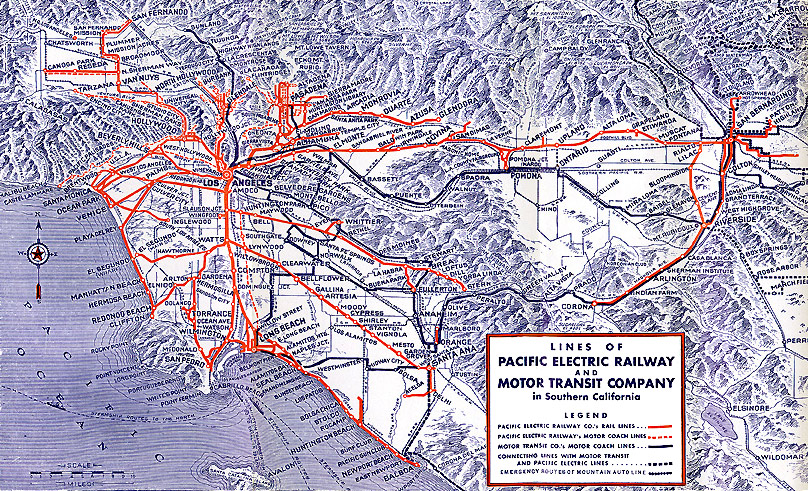

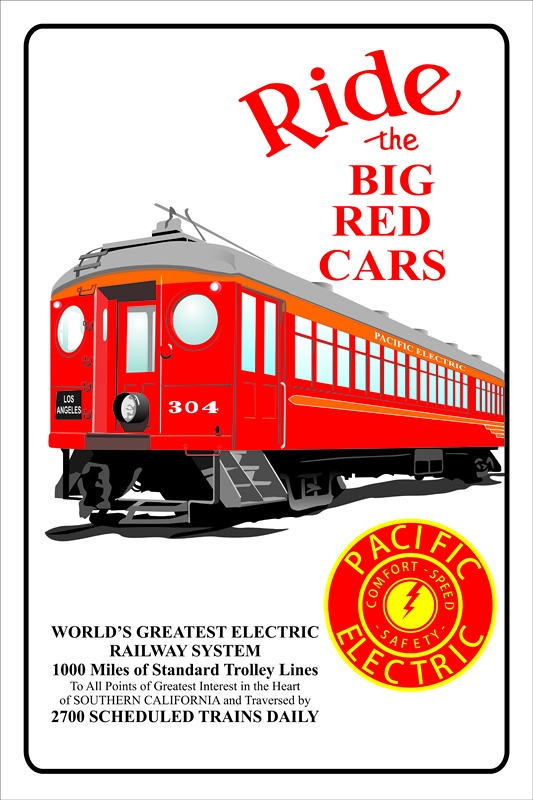

Indeed, Southern California’s Pacific Electric interurban streetcar system was a world leader in public transit in the early decades of the twentieth century. In his 1971 book, Los Angeles: the Architecture of Four Ecologies, author Reyner Banham states, “The Big Red Cars ran all over the Los Angeles area — literally all over.” And in The Electric Interurban Railways in America, historians George W. Hilton and John F. Due placed the Los Angeles network as “the largest intercity electronic railway system in the U.S.,” covering 25 percent more mileage than today’s New York City subway.

But in a twist of irony, Eddie Valiant’s simple declaration of LA’s transit supremacy presages the demise of this once mighty electric railway system.

Henry Edwards Huntington was born on February 27, 1850, in Oneonta, New York. Having grown up hearing about his uncle, Collis P. Huntington – one of the “Big Four” founders of the Central Pacific Railroad – Henry would eventually go to work for his uncle, holding several executive positions under him with the Southern Pacific.

Henry Huntington had anticipated that when his uncle Collis died, he would assume control of the Central Pacific and Southern Pacific, but this move was blocked by one of the railroads’ major bondholders, and Henry was forced to sell his interests to E. H. Harriman.

Electric trolleys had first appeared in Los Angeles, California in 1887. By the mid-1890s, through various mergers with other local railways, electric streetcar service reached from the mountains of the San Gabriel Valley, to the coast at Santa Monica.

In a good-natured competition with his uncle’s Southern Pacific, Henry Huntington purchased the narrow gauge Los Angeles Railway (LARy) in 1898. When his plans to succeed his uncle were frustrated following Collis’ death in 1900, Huntington shifted his focus to building up a Southern California-based interurban streetcar system, and in 1901 formed the Pacific Electric Railway.

“She used to go out with the girls

Every now and then

She always came home early

We’d jump in bed by ten

She’d tell me that she loved me

She would forevermore

But that train don’t stop here anymore” – Rosas / Preston

Huntington’s enterprise succeeded by providing passenger-friendly interurban streetcar service on regular daily schedules that the railroads could not equal. Organized around the city centers of Los Angeles and San Bernardino, Pacific Electric connected towns in Los Angeles County, Orange County, San Bernardino County, and Riverside County. By 1910, the system spanned approximately 1,300 miles of Southern California. In a short period of time Pacific Electric Railway’s “red cars” had become iconic and ubiquitous.

The expansion of Pacific Electric’s area of operation coincided with an explosive development boom in the Los Angeles Basin, Orange County, and the Inland Empire. In actuality, the enormous amount of growth was spurred by the transit system itself. Aside from his function as the head of the railway, Henry Huntington had also invested heavily in real estate in the areas in which he had been purchasing smaller municipal transit systems which would, in turn, become part of his larger Pacific Electric system.

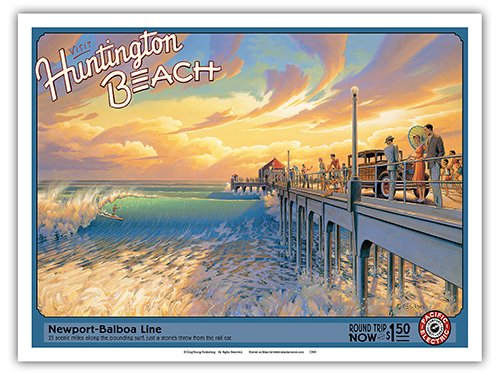

The city of Huntington Beach, California, incorporated in 1909, was developed by the Huntington Beach Company (formerly the West Coast Land and Water Company), a real-estate development firm owned by Henry Huntington. Although the company is now wholly owned by the Chevron Corporation, it still retains both extensive land holdings in the city and most of the mineral rights. In the words of author James Howard Kuntsler, the Pacific Electric Railway “connected all the dots on the map and was a leading player itself in developing all the real estate that lay in between the dots.”

The tremendous increase in Southern California’s population during the early decades of the twentieth century had the PE’s red cars connecting communities with rich ethnic and cultural diversity. The community of Watts lies due south of downtown Los Angeles, and although originally developed as an independent city, it is now part of the South Los Angeles region. The neighborhood saw rapid development with the opening of Pacific Electric’s Watts station in 1904. Sitting roughly halfway between the city center and the harbors at San Pedro and Long Beach, Watts served as a “key junction and interchange between the long-distance trunk routes, the interurbans and street railways,” observed Reyner Banham, and it “is doubtful if any part of Greater Los Angeles, even downtown, was so well connected to so many places…”

By 1910, Watts’ nearly 2,000 residents included Germans, Scots, Mexicans, Italians, Greeks, Japanese, and blacks from the American South. Many of these residents used Pacific Electric to commute to downtown jobs. Jazz saxophonist, Cecil “Big Jay” McNeely, a native Los Angelino and veteran of the clubs located along the city’s Central Avenue, remembers “[We] had the ‘big red’ that would go out to Pasadena, big red to San Pedro, big red to Long Beach. They ran so fast, so it didn’t take you any time to get there.” Other regular red car riders included jazz musicians Charles Mingus and Buddy Colette, who rode the car from Watts to Los Angeles. On some rides, impromptu jam sessions would spring up. “Mingus would always take the cover off his bass and urge Buddy to jam with him during the ride,” remembered musician Red Callendar. “Instead of being bothered, the passengers loved it.”

“Big Jay” McNeely

Charlie Mingus

Buddy Colette

The Pacific Electric contributed to the development of other “streetcar suburbs” including Angelino Heights, Highland Park, Van Nuys, Marion (now Reseda), Owensmouth (now Canoga Park), and West Hollywood. Real estate developers promoted the PE’s “Balloon Route,” so-called for the shape that the route traced traveling from downtown to the beach towns and back again. Posters advertised Venice Beach as “the Coney Island of the West,” Redondo Beach as the “happy medium for the masses” and Huntington Beach as the “rendezvous for little families.”

I remember my late father sharing with me his experiences riding the red cars as a young man. In his teen years and early adulthood my father had lived in the city of Huntington Park – another of the streetcar suburbs named for Henry Huntington – and he told me of the times that he would ride the Pacific Electric from his home to the beach, where he would spend the day before riding back again, all for the price of a nickel each way. Having shared this memory with me on a number of occasions, I sensed that it may have been a particular source of nostalgia for him.

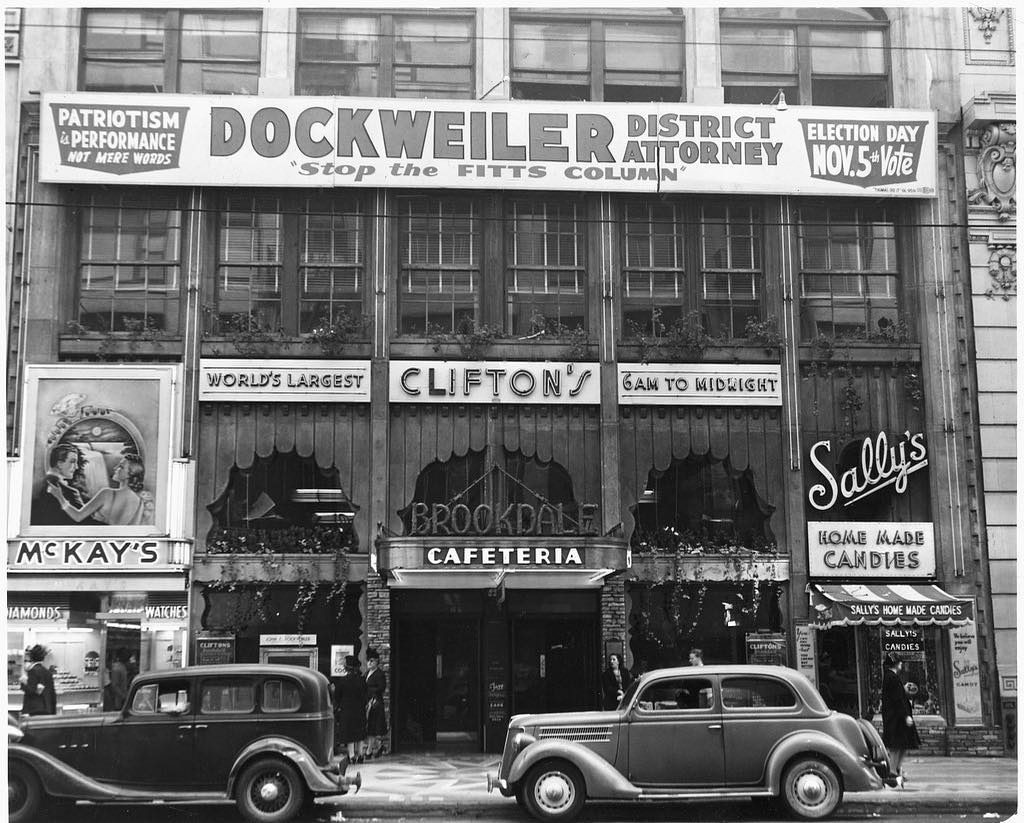

As I was preparing to write this post, I asked my ninety-three-year-old mother, who grew up in the city of Compton, if she had any distinct recollections of the Pacific Electric red cars. She responded, “I certainly do!” She remembered riding the red car into downtown Los Angeles along with her mother and younger sister, to do as she described it, “big shopping.” After the shopping was done, her mother treated the girls to lunch at Clifton’s Cafeteria.

My mother stressed that getting to ride the streetcar into downtown LA, as well as getting to eat lunch there, was a very special occasion. As she related this memory to me she remarked that she could clearly remember the sights, sounds, and smells of those old wooden cars: the ringing of the bell as the cars arrived and departed the platform; the doors clanging open and closed, and the vibrations of the rails felt through the unpadded wooden seats. She also remembered her father driving them to and from the streetcar platform on Alameda St in Compton.

“Nothin’ changes faster

Than baby’s fickle mind

I know she’ lovin’ someone

Somewhere down the line

I know that she still has a key

I’m waiting by the door

But that train don’t stop here anymore

Anymore, anymore, anymore, hey” – Rosas / Preston

Over the years there has been much talk of a conspiracy to dismantle Los Angeles’ interurban transit system in favor of automobile travel. As mentioned at the top, this is an integral plot point in the film Who Framed Roger Rabbit, when the Pacific Electric Railway Co. is sold to the shady Cloverleaf Industries, and its sole shareholder is revealed to be the sinister Judge Doom. In real-life, the conspiracy played out as the Great American Streetcar Scandal, when in 1974 the U.S. Senate heard allegations of General Motors’ and other companies’ involvement in the break-up of streetcar systems across the United States and in particular in Los Angeles.

In truth, revenue from passenger traffic rarely generated a profit, unlike freight. As Henry Huntington’s involvement with urban rail was so closely associated with his real estate development, where profits had been significant, many lines on the Pacific Electric’s system had ultimately been run at a loss. But by 1920, when most of their real estate holdings had been developed, the major income source began to dry-up.

The 1930s saw the coming of freeways, while the Interstate Highway System of the 1950s was looming on the horizon. The bulk of Pacific Electric’s inner-city tracks shared streets with automobiles and trucks, and as traffic congestion increased, the speed and efficiency of the streetcars began to decline. Incrementally lines were sold off and eventually replaced by bus routes.

“She ran out through the back door

Screamin’ in the night

She said I was the devil

I didn’t treat her right

The man down at the station

Said that was her for sure

Now that train don’t stop here anymore

Anymore, anymore, anymore” – Rosas / Preston

April 9, 1961, saw the final ride of LA’s celebrated red car. The run took place on the Los Angeles-to-Long Beach line, which having begun operation on July 4, 1903, held the distinction as being the Pacific Electric Railway’s first and last interurban passenger line.

“Now that train don’t stop here anymore” – Rosas / Preston

But just as everything that’s old is new again, in 1990 the Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority opened the A Line (formerly the Blue Line) on the very same right-of-way as the old Pacific Electric route. As of December 2017, the 22-mile route from LA to Long Beach had an estimated 22.38 million riders per year.

Thanks to Los Lobos – way more than “just another band from East L.A.” – for providing the inspiration for this post. Their story is as much a part of the fabric of the “City of Angels” as is the story of Pacific Electric’s legendary red cars. And while that “train” may not stop here anymore, Los Lobos continue to make outstanding music that ably represents their hometown of El Pueblo de Nuestra Señora la Reina de los Ángeles.

Sources:

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pacific_Electric

https://www.scpr.org/news/2016/05/19/60798/before-the-shiny-expo-line-extension-there-was-the/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Los_Lobos

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kiko_(album)

All photos sourced through internet searches, none belong to the author

Keep up the good work.