“Well I woke up this morning

And the sun refused to shine

I knew I’d leave my baby

With a troublin’ mind

It rains every morning

And evening is the same

And it’s gonna be a long time

‘Til I hear the 2:10 train” – 2:10 Train (Albertano / Campbell)

Ever since the dawn of human life on this planet, brilliant minds have devised methods by which to measure the passage of time: tracking the sun, and other celestial bodies; counting the flow of sand through a narrow neck of glass; water clocks, candle clocks, and time sticks. But all of these practices left room for great variation, and time, or the measure of, was far from uniform.

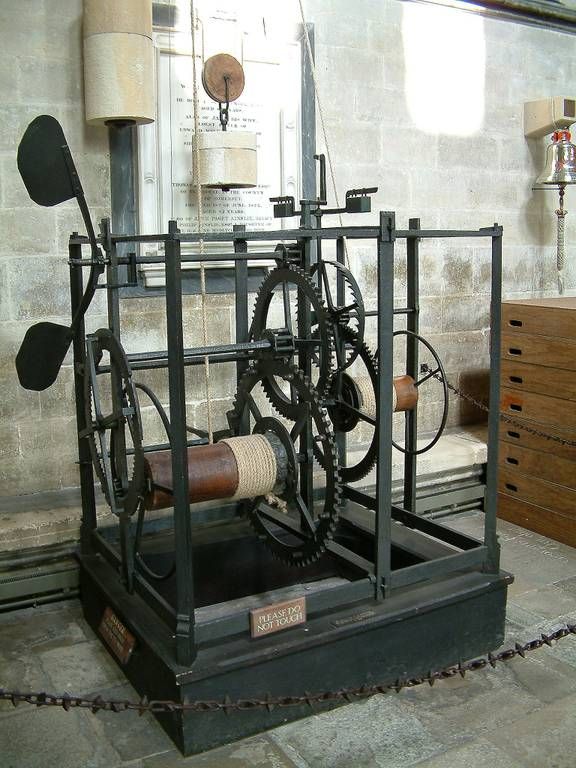

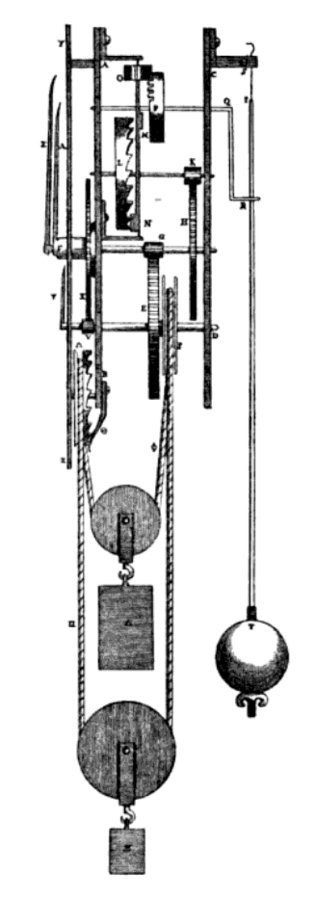

Not until the early 14th century did mechanical timekeepers appear; followed several hundred years later by the pendulum clock, and with the invention of the mainspring, portable clocks soon evolved into pocket watches.

But even as the more reliable timekeeping mechanisms of the Industrial Age allowed for the increasingly more accurate measure of time, there was still plenty of room for fluctuation from place to place, and the coming of the railroad introduced an immediate need for time standardization.

“Inside outside, leave me alone

Inside outside, nowhere is home

Inside outside, where have I been?

Out of my brain on the 5:15” – 5:15 (Pete Townshend)

In England, a standardized system known as Railway Time was first adopted by the Great Western Railway in November 1840. This was the first occasion in which local mean times were synchronized to a single standard time. Over the next several years Railway Time was progressively adopted by all the railway companies in Great Britain, and by 1855 the electric telegraph allowed for all stations along all railway lines throughout the country to be synchronized to Greenwich Mean Time.

Prior to the adoption of Railway Time, each town in England would synchronize their local time according to a public clock, usually located in the town square, courthouse, or church. Until the latter part of the 18th century, these clocks were set by solar time, using a sundial. Understandably this left room for significant variance in time from town to town.

As travel in that period was often undertaken by foot, by horse, or by carriage,

While it may be easy for us today to see the sound judgment in having uniform time throughout a country, the railway companies initially encountered resistance in many towns, where it was not uncommon to find two different times displayed and in use. A railway station clock would often show a time that could differ by several minutes from other clocks in town. In spite of the early reluctance, Railway Time was soon adopted by the entire country, although the government did not legislate a single Standard Time and single time zone for Great Britain until 1880.

“I lost everything I had in the ’29 flood

The barn was buried ‘neath a mile of mud

Now I’ve got nothing but the whistle and the steam

My baby’s leaving town on the 2:19” – 2:19 (Brennan/Waits)

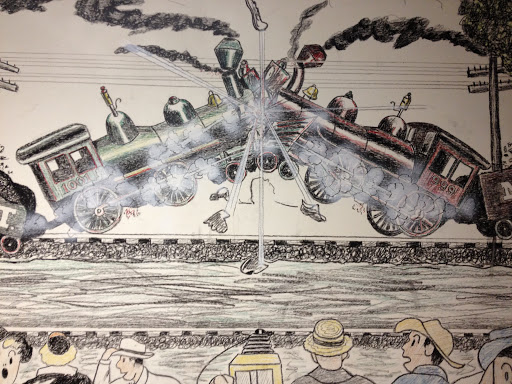

In New England, in August of 1853, two trains collided resulting in the death of 14 passengers. The trains were traveling towards each other on the same track, with the collision resulting from the individual train guards having different times set on their watches. Soon railway schedules were coordinated throughout New England, but numerous other accidents led to the need to set up a General Time Convention, which was a committee comprised of railway companies to agree on scheduling.

“I want to ride again

On the 3:10 to Yuma

That’s where I saw my love

The girl with the golden hair” – 3.10 to Yuma (Washington/ Dunning)

At Promontory Point in Utah, on May 10, 1869, a crowd had gathered to witness the driving of the final, ceremonial golden spike, which would join the Union Pacific & Central Pacific Railroads into what would become known as the transcontinental railroad. Telegraph wires had been attached to both the

Gathering at noon, the crowd waited 45 minutes for Leland Stanford to raise the silver maul, and drive the golden spike. The moment was recorded as 12:45 p.m. at Promontory Point, 12:30 p.m. in Virginia City, both 11:44 and 11:46 a.m. in San Francisco, and 2:47 p.m. in Washington D.C.

At the time that the two railroads were joined to form the transcontinental railroad, more than 8,000 towns were using their own local time over 53,000 miles of track that had been laid across the United States.

“Eight-oh-five

I guess you’re leaving soon

I can’t go on without you

Eight-oh-five

I guess you’re leaving…goodbye” – 8:05 (Laura Anne Stevenson)

In

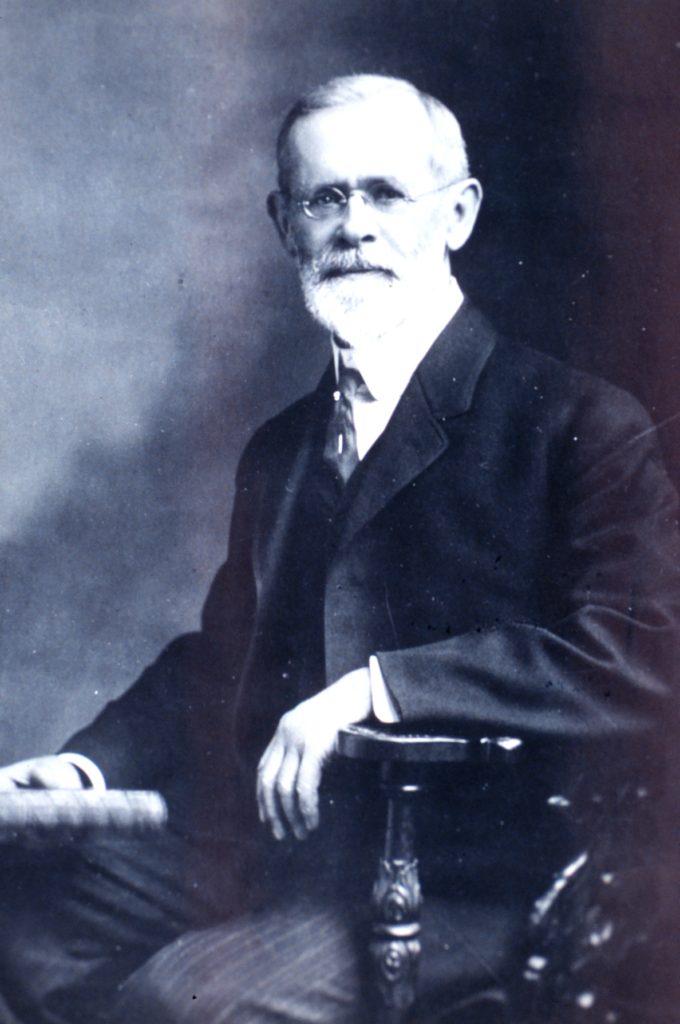

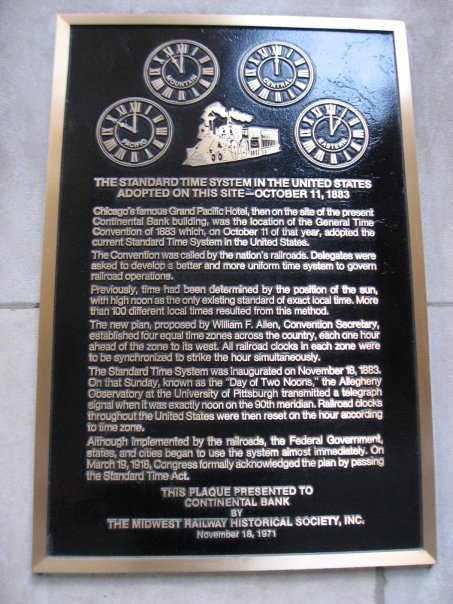

Cleveland Abbe, who in 1871 was appointed chief meteorologist at the United States Weather Bureau, subsequently divided the continental United States into four standard time zones, in order to institute a time-keeping system that was consistent between the nation’s weather stations. In 1879 he published a paper titled Report on Standard Time, and in 1883 was successful in convincing the General Time Convention and North American railroad companies to adopt his time-zone system, replacing the 50 different railway times that were then in use.

Surely it would seem the wisdom of this standardized system is self-evident, but there were many smaller towns and cities that were opposed to the adoption of Railway Time. An 1883 report in the Indianapolis Daily Sentinel complained that people would have to “eat, sleep, work … and marry by railroad time”. However, with the support of nearly all railway companies, most cities, and nationally influential scientific institutions, Standard Railway Time was introduced in the United States at noon on November 18, 1883.

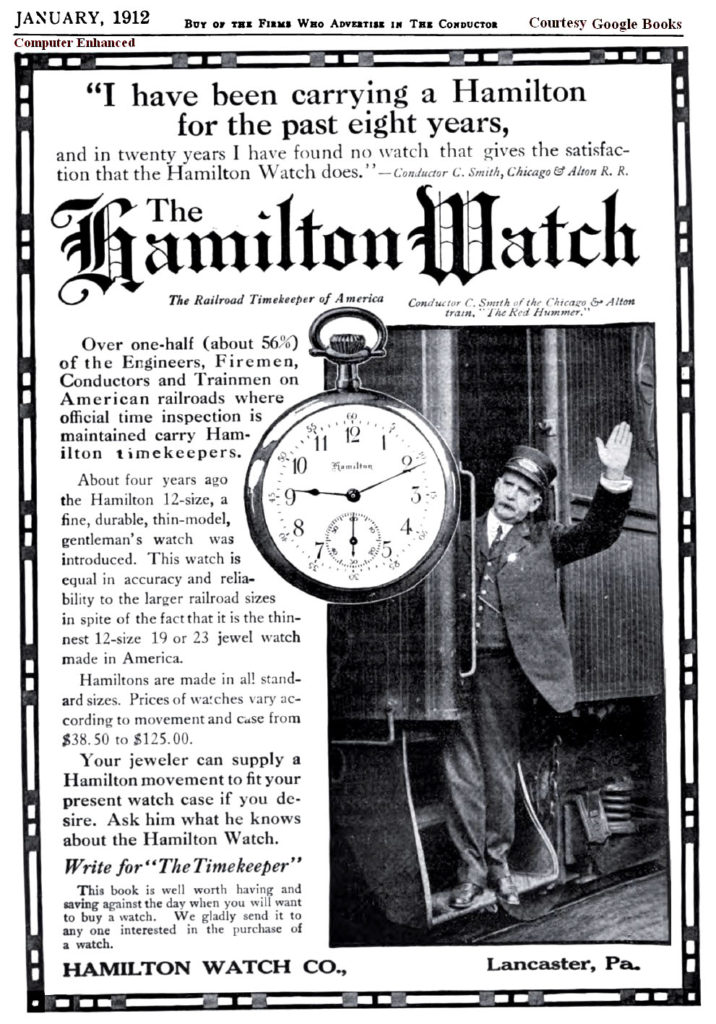

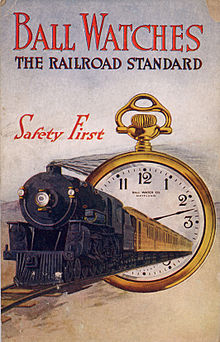

Through the ensuing decades, Railway Time became a trusted standard, generally accepted as being highly reliable and accurate; departure and arrival times became an embodiment of train lore as much as any other aspect of railroading. Why even bother writing a song about it if you were not fairly certain that your train would be on time?

“5:15, I’m changing trains

This little town, let me down

This foreign rain brings me down

5:15, train overdue

Angels have gone, no ticket

I’m jumping tracks, I’m changing time” – 5:15 (The Angels Have Gone) David Bowie

Sources:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Railway_time

https://railroad.lindahall.org/essays/time-standardization.html

All photos sourced through internet searches, none belong to the author.

Thanks, Clifton Gilley for crburganmusic.com