“In an era of dissension

On a bleak mid-winter morn

There stood a house divided

By righteous indignation borne” – Chunky Creek (Train Wreck of 1863) © C. R. Burgan, Jr. / BMI

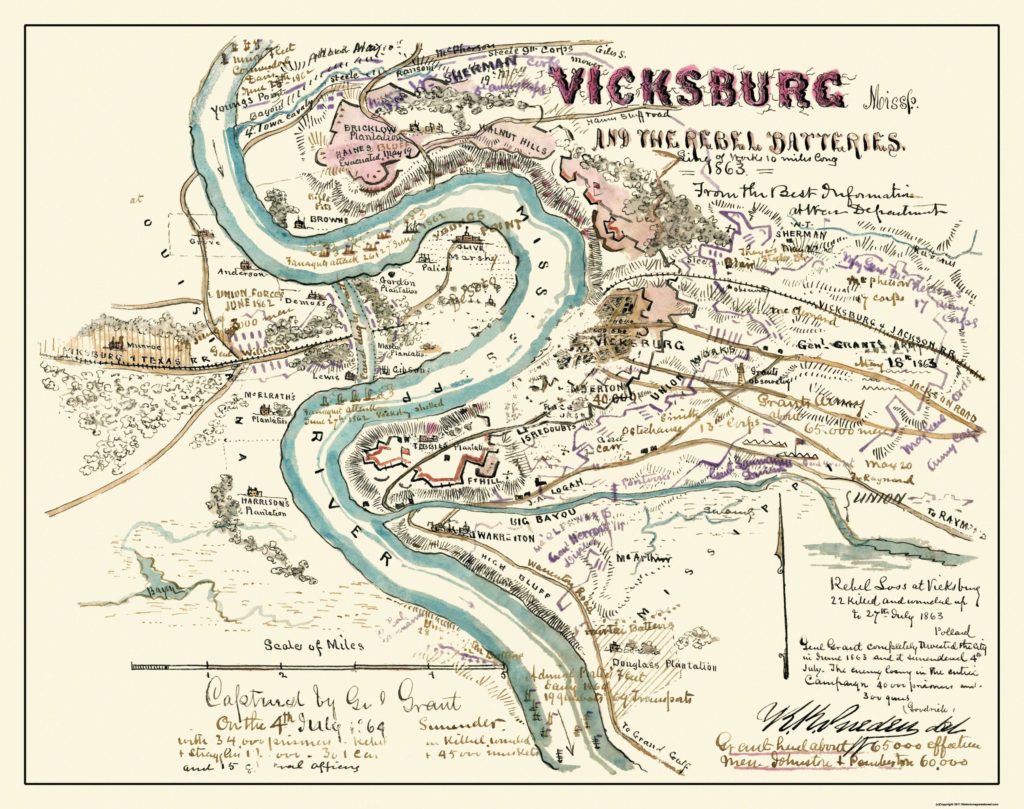

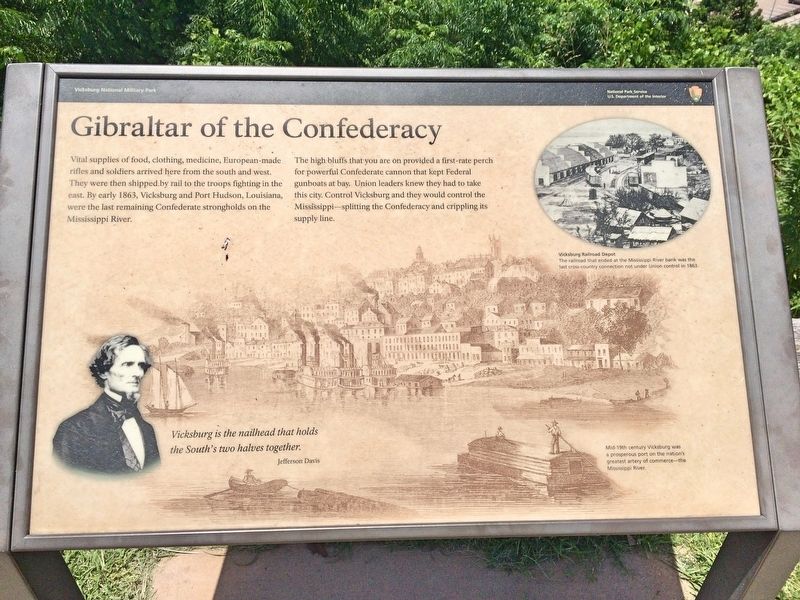

The winter of 1862 – 63 saw a number of attempts by the Union army to wrest control of the city of Vicksburg, Mississippi from the Confederates. The city had become a fortress for the Confederate States, allowing the South to control the southern portion of the Mississippi River, as far as Port Hudson, in Louisiana. The city’s natural riverside defenses were perfect, earning it the nickname, “The Gibraltar of the Confederacy”. Located high on a bluff overlooking a horseshoe-shaped bend in the river, Vicksburg was almost impossible to approach by ship.

With the city of Memphis having fallen to Union forces the previous summer, the strategic importance of maintaining control of the lower Mississippi River could not be overstated. President Jefferson Davis had declared, “Vicksburg is the nail head that holds the South’s two halves together.”

Jefferson Davis

Abraham Lincoln

The Union also understood the significance that control of the Mississippi represented to the Confederacy in maintaining a supply line with their states on the western side of the river. In Washington, President Abraham Lincoln had written, “Vicksburg is the key. …The war can never be brought to a close until that key is in our pocket”.

Vicksburg had been under Union attack previously when in the spring of 1862 Admiral David Farragut traveled upriver after his capture of New Orleans. Demanding the surrender of the city, but lacking sufficient troops to force compliance, he returned to New Orleans. Likewise Union naval attacks arriving from the north had also failed due to the gunboats being unable to approach the city while remaining out of reach of Confederate gun emplacements upon the bluff.

Realizing the impregnable nature of the city’s riverside defenses, the Union soon commenced an overland campaign to attack Vicksburg from the east.

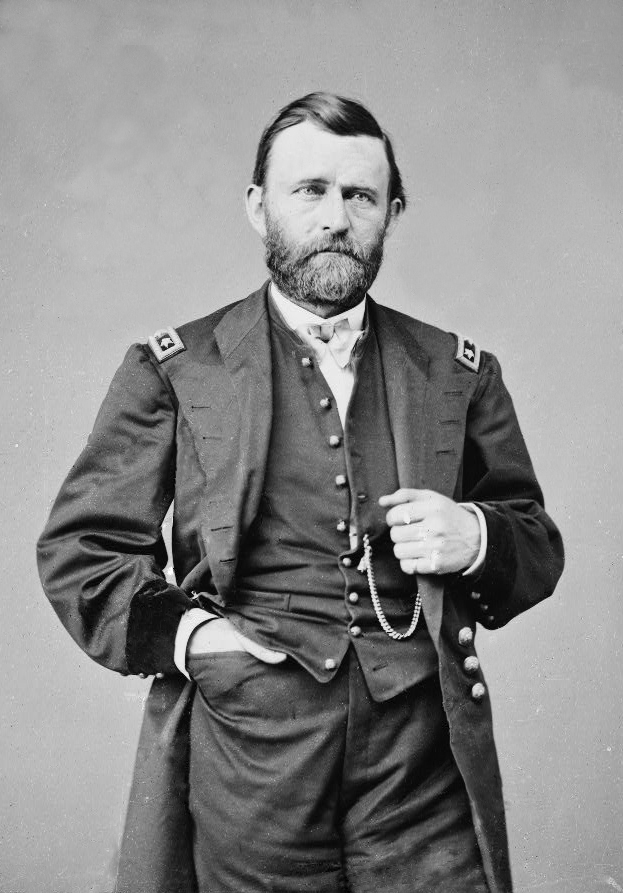

Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, U.S. Army

Gen. John C. Pemberton, CSA

Defending the city of Vicksburg, Lt. General John C. Pemberton commanded what historian John D. Winters described as “a beaten and demoralized army, fresh from the defeat at Corinth, Mississippi”. If there was any hope of holding the city against General Ulysses S. Grant and the Army of

“The driver gave the order,

‘Stoke that fire in the belly of the beast!’

With his consignment of souls, supplies & cash

He set out from the east” – Chunky Creek © C. R. Burgan, Jr.

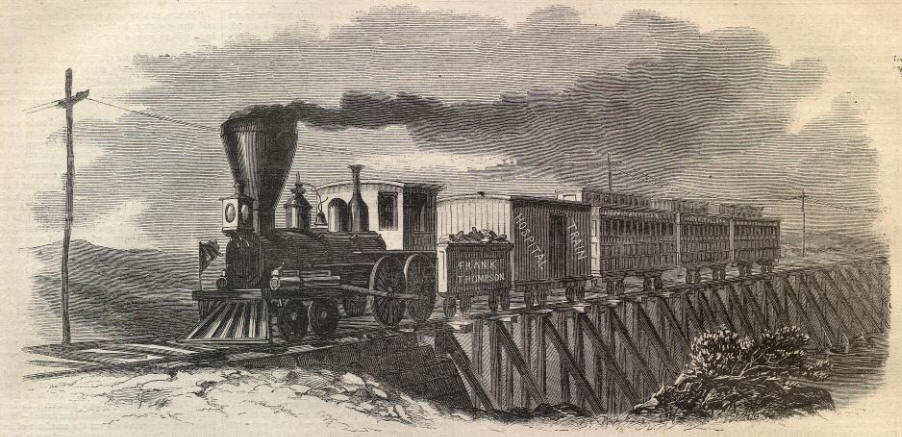

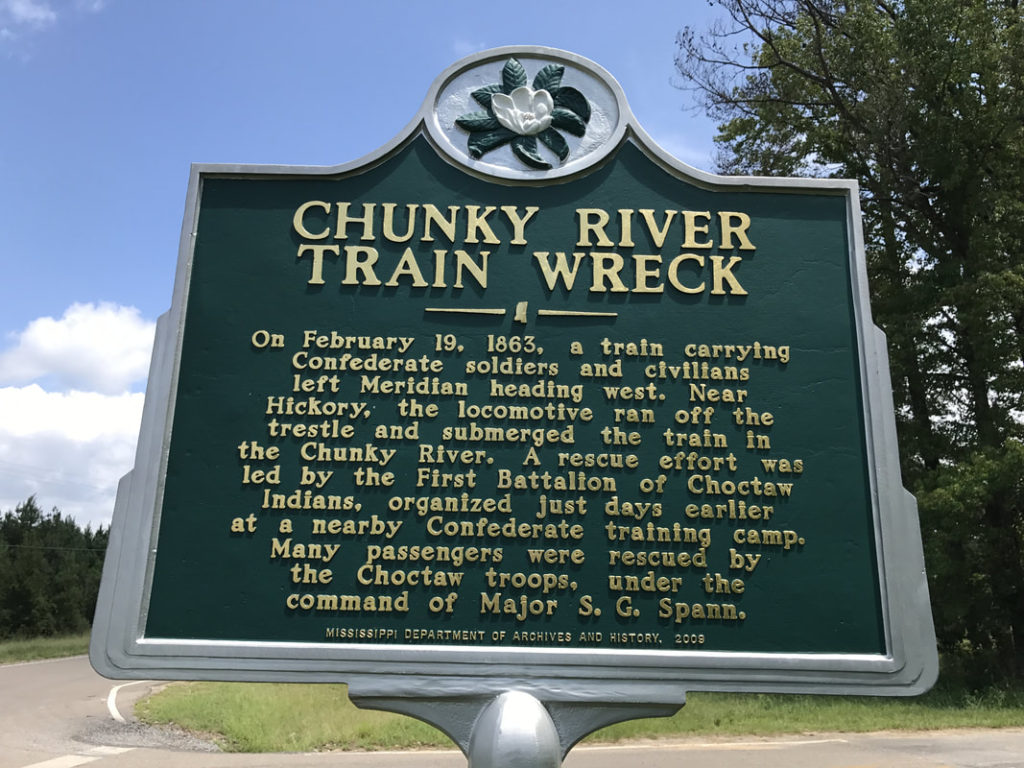

In the early morning hours of February 19, 1863, a train carrying Confederate soldiers and some civilians departed from Meridian, Mississippi, bound for Vicksburg. Along with the passengers the train also carried supplies and a large amount of cash. Due to the battles being waged in the Union’s campaign for control of the river port, there was a great urgency to receive the train and its manifest.

The consist was led by an American 4-4-0 type locomotive known as Hercules; the engineer was Isaiah P. Beauchamp. Prior to the war both locomotive and driver had been based in New Orleans, Louisiana. On this date Hercules was pulling a tender and four cars, with 100 passengers aboard.

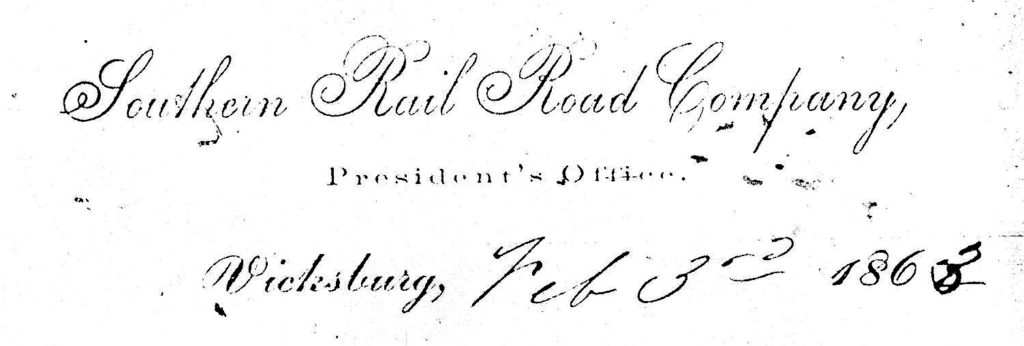

For months the region had been experiencing heavy rains which had caused the Chunky River to flood repeatedly. Each successive flooding brought more debris downriver, much of it coming to rest against the wooden pilings and trestles of the Southern Rail Road bridge that spanned the waterway.

The Southern Rail Road had acquired a reputation for having one of the least well-maintained trackages in the country. The Daily Southern Crisis, a newspaper in Jackson, reported that accidents on the line were a common occurrence.

A train had crossed the Chunky bridge a day ahead of the Hercules, but only after all the passengers had been removed from the train, with the train proceeding to slowly cross over the swollen river. It is believed that this train crossing may have caused the bridge to shift, settling to as much as 6 inches out of alignment with the rails on the eastern side of the span. Efforts were made to repair the bridge, but there was not an adequate crew to perform the work before the next train was due.

Absalom F. Temple was the section master for an approximately

Temple’s account was printed in The Daily Southern Crisis:

“ . . . I told him to be sure and keep a negro there for the purpose. I then dug a hole in the middle of the track and put up a thick pole about as near as I could tell 150 yards from the bridge. This is the usual method of stopping trains when danger is ahead . . . The next morning I had the hands up before daylight, and was just going out on the road to work . . . Just as I started out I met a man running up the road with the news of the accident”.

“Scoured from the landscape

And hastened by the flood

The detritus of a region swirled

And mixed with sweat and blood

“Pilings yielded to the pressure

The Chunky’s span no longer true

And the Mississippi Southern plunged into the flow

In its effort to push on through” – Chunky Creek © C. R. Burgan, Jr.

Hercules ran off the track as it entered the bridge, becoming completely submerged in the icy cold water. The tender and trailing cars landed on top of the locomotive, with the wooden cars being nearly demolished by the impact. Barrels and boxes were later found floating downstream.

The Athens Post, a newspaper based in Athens, Tennessee printed the following report:

“A man just in from Chunkey (sic) says the engine and five cars are under water.— the

“With brazen disregard for self

Dark schemes to circumvent

Came brave delivering angels

Most surely heaven sent” – Chunky Creek © C. R. Burgan, Jr.

Camped near the crash site happened to be a newly formed regiment, the 1st Battalion of Choctaw Indians. Hearing the commotion the soldiers rushed to the riverside, stripped down and immediately jumped into the water and began removing bodies. Samuel G. Spann, a captain at the time later reported in a magazine article that “ninety-six bodies were brought out upon a prominent strip of land above the waterline. Twenty-two were resuscitated . . . and all the balance were crudely interred upon the railroad right of way, where they now lie in full view of the passing train

“The ultimate tribute offered

The utmost price was paid

Now their silent mortal vessels

Along the right of way are laid” – Chunky Creek © C. R. Burgan, Jr.

Most of those that perished were either killed by the initial impact or trapped underwater beneath the wreckage. Of the one hundred passengers on the train, seventy-five perished, including the engineer, who had been trapped within the locomotive. A small number of the bodies were eventually disinterred by family or friends, but some remains were unable to be located due to the crude manner in which they were originally buried. A marker has been placed at the site to commemorate those whose lives were lost in the wreck.

I came upon an accounting of this incident inadvertently, and believing that the story of the train wreck was little known I set upon telling it in my own way. While some artistic license was taken, I hope that I have been faithful to the details, and the memory of those whose lives were lost.

“You can’t cheat Mother Nature

Of the toll that she demands

The blood will let as you place your bet

And you leave it in the devil’s hands

And where the wheel stops turning

Only the Maker knows . . .

The muddy river flows” – Chunky Creek © C. R. Burgan, Jr.

Sources:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Siege_of_Vicksburg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Siege_of_Port_Hudson

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vicksburg_campaign

https://www.nchgs.org/html/train_wreck_1863.html

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chunky_Creek_Train_Wreck

All photos sourced through internet searches, none belong to the author.

Love it, CR! Keep writing, my friend.

Thanks, Ed. Keep reading!